Two for the price one: do artist pairings ever work?

Two new London exhibitions proffer the same idea, with very different results.

Something isn’t quite right. That’s what I thought when I went to see Kiefer / Van Gogh, the latest show at the Royal Academy. Both it and the Barbican’s Encounters: Giacometti x Huma Bhabha follow the same curatorial strategy: juxtaposing works by artists from two different periods.

You can see the symbiotic relationship at play. It’s a formula. On one side, the legendary name attracts attention and brings in the crowds, on the other, the inclusion of contemporary art allows the curators to show the older master in a new light, and in doing so, hopefully, lure a younger generation of visitors.

Van Gogh is more than a household name – he’s the epitome of the tortured artist, with a missing ear to boot. This isn’t the first time his works have been set alongside those of a contemporary painter.

The Van Gogh Museum (Amsterdam) is currently showing Van Gogh x John Madu: Paint Your Path, staging the Dutch master’s work in conversation with the Nigerian artist. Last year, Matthew Wong / Vincent van Gogh: Painting as a Last Resort, saw the colourful works of the Chinese-Canadian artist placed next to everyone’s favourite impasto landscapes and still-lives. And there are more examples.

At the Royal Academy, the artist chosen is Anselm Kiefer. Born in Germany, he now lives in France.

For the last 60 years, he has been using materials such as straw, clay and shellac to create large-scale paintings and sculpture centring on the themes of World War II and Holocaust. His paintings sell for millions and grace both private collections and grand public museums, from MOMA to Tate Modern.

He also, at some point, had a studio large enough for him to need a bike to get around. At the current show, you can see why.

Entering this three-room exhibition, you are faced with one of Kiefer’s characteristic, gargantuan canvases. In fact, the room has four – one on each wall. And then, in the far-right corner, small by comparison, a rather unusual Van Gogh: a painting of a pile of books.

Kiefer’s works depict landscapes, birds and flowers, but they’re not as cheery as they may sound. All his paintings are imbued with a feeling of loss and unease. There is a poignant absence of humans. Empty roads, black birds, black flowers – they all point to an insurmountable darkness.

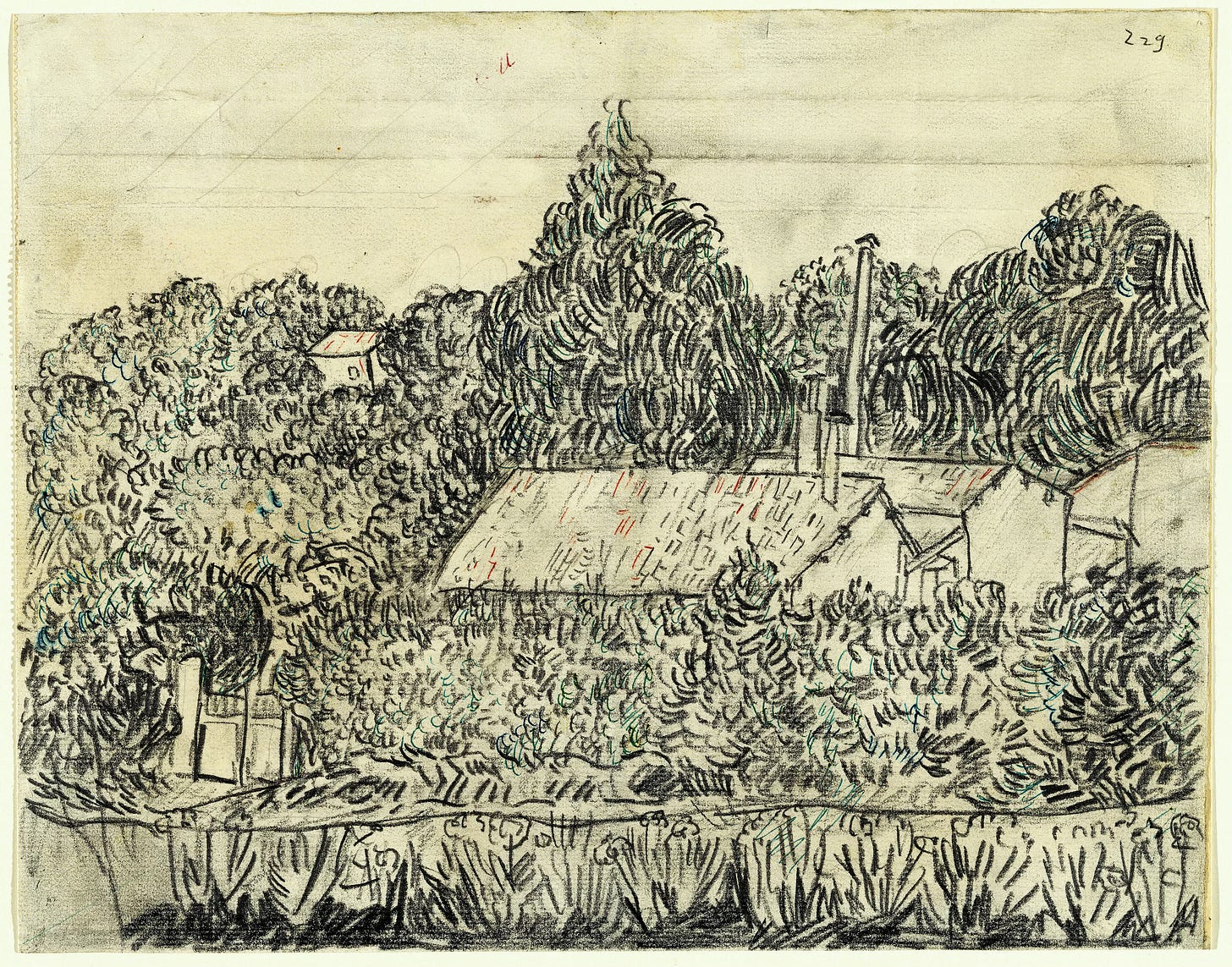

Kiefer was undeniably influenced by Van Gogh. At age 18, in 1963, he made something of a pilgrimage through places associated with the older artist in the Netherlands, Belgium and France. The booklet accompanying the exhibition is a collection of Kiefer’s diary entries from that time. We sense his strong infatuation with Van Gogh, but also his naïve disappointment that things weren’t as they were back in Vincent’s time. (He found that people were wearing modern clothing!)

The exhibition highlights some similarities between the two artists: most notably the sunflower motif; also their use of heavily-textured paint. Some works, such as the drawings in the second room and a massive gold-painted The Starry Night at the end, are directly inspired by those of Van Gogh. I personally don’t find the last one appealing: it sacrifices what is great about Kiefer yet can never emulate what was great about Van Gogh.

The whole show leaves both artists betrayed. There seems to be not enough Van Gogh. Even though there are eleven of his works, many are drawings, and they all seem squashed under the weight of Kiefer’s monumental canvases. At the same time, Kiefer’s oeuvre seems almost secondary in quality – repetitive of both himself and the older artist.

Would I advise you to go? Probably. These are two immensely important artists put in conversation. Each work individually provokes a ‘wow’. But I’d also like to know your opinion on the dialogue…

Encounters: Giacometti x Huma Bhabha is more like a conversation between friends. Giacometti is synonymous with Post-War European art. His works are metaphors for the desolate human condition afterthe war ended. Long, shadow-like figures walk and stand, alone or in groups – but always lonely.

Huma Bhabha picks up where Giacometti left off. Her works are about a perpetual war. Her sculptures suggest body parts – feet, legs, heads. They are lying, sitting or walking with no purpose or sense of destination, like human carcases.

Her shapes seem to be walking on the same desolate streets as Giacometti’s – as lonely as one another, they ignore each other, their pain unshared. But for the viewer, they amplify one another, give space and add volume.

The show takes place in the Barbican’s new exhibition space. The far side of the gallery is not a wall, but a window. It’s not a clean-lined, uniform, white gallery space; it brings the outside in.

This way, the sculptures are given a new setting every time the sun moves. Both the weather outside and the time of day change the lighting of this ‘natural’ background. Now the shadowy figures are walking in the modern day. They are no longer just in the past, just somewhere else, just art – they are messengers bringing a warning.

Bhabha, originally from Pakistan, now lives in New York. Like Kiefer, she uses a variety of materials, including rubber, cork and styrofoam. Some works are then cast in bronze, including the four sculptures that are placed right outside the Barbican show – you don’t need to pay to see those. They’re quite different from the ones inside. More monumental in scale, they look like a combination of sci-fi aliens and the remnants of an ancient civilization.

Giacometti is going to be paired with three different artists during this year-long exhibition; Huma Bhabha is but the first. She’ll be followed by Mona Hatoum in September and then Lynda Benglis in February 2026. This first iteration is worth a visit if you are in the neighbourhood. It’s not a large show, but it makes you think. I have high hopes for the other two as well.

In case you haven’t guessed, I’m a little ambivalent when it comes to shows that put works by very famous artists next to others. To my mind, there’s always a suggestion that one is more important.

Sometimes they backfire: revealing, or confirming, that the great artists aren’t great for nothing, and that others don’t quite match up. Occasionally it feels like their art and legacy are abused and overused.

At other times, these pairings suddenly prompt a new way of seeing what we thought we knew through and through. The two current shows are offering their own takes on this trope. And I think one did it better. What do you think?

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy, London, 28 June – 26 October 2025.

Encounters: Giacometti, Barbican, London, 8 May 2025 – 24 May 2026

another brilliant review- such a great read, thank you. One of the loveliest sentences I have come across lately is here: "This way, the sculptures are given a new setting everytime the sun moves" So poetic.